By Dave Schilling—May 3, 2017

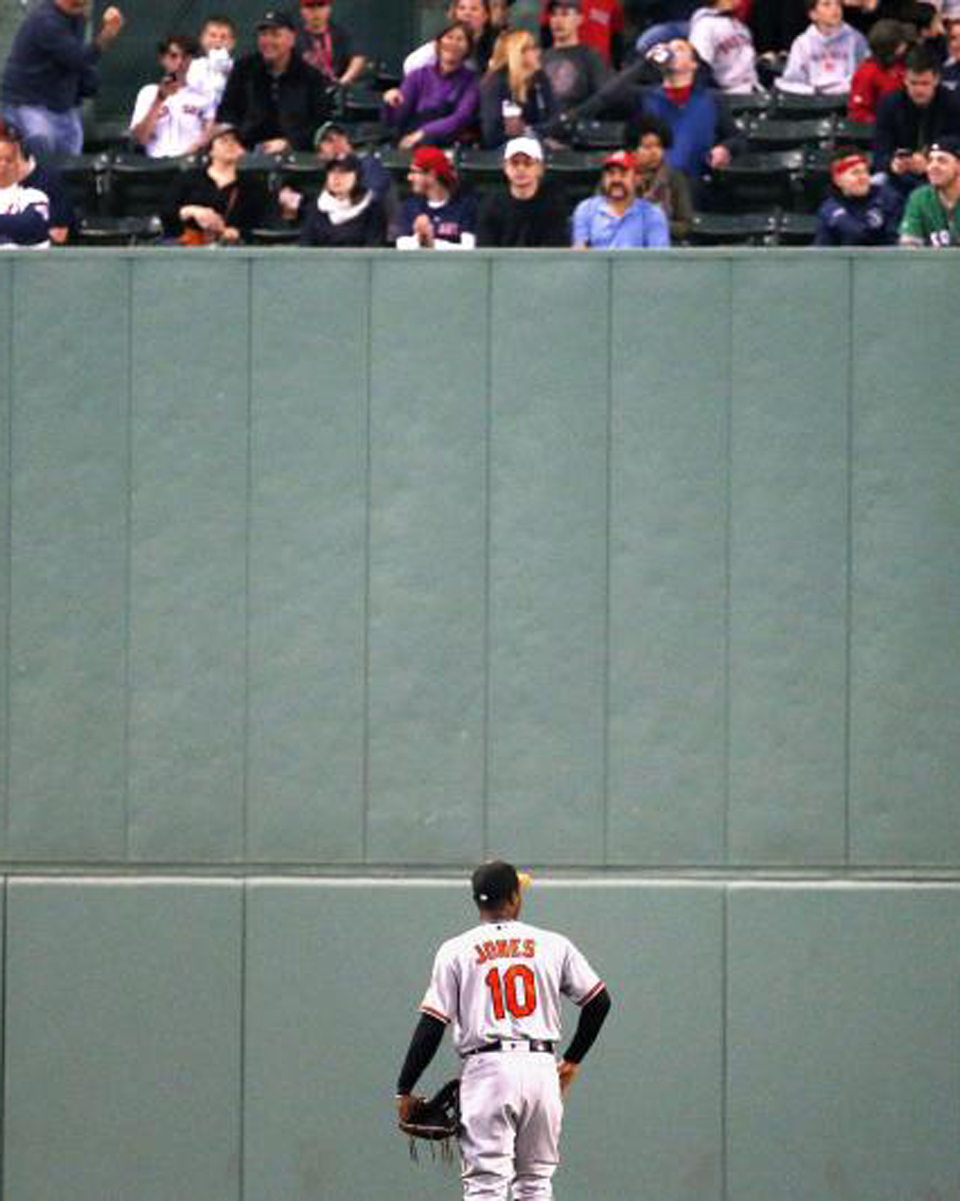

Adam Jones getting a standing ovation at Fenway Park on Tuesday was a moment. We love moments. Sports, after all, is a collection of them more so than games, seasons, or even careers. You remember Jordan’s jumper over Craig Ehlo like it happened 20 seconds ago, but how much of that actual game can you recall from memory? A moment can be a shorthand for an emotion or a symbol for something greater, which Colin Kaepernick understood when he sat for the playing of the national anthem. It can be more powerful than any word spoken, at least that was the hope Tuesday as the Red Sox faithful stood to shower Jones with affection the day after a single word made him national news.

The thing we often forget about moments, though, is what has led up to them. What was the score of that Bulls/Cavs game? Why was Jordan’s shot so important and why was it so devastating to Cleveland? Why is someone calling a baseball player the N-word in Fenway Park so shocking and reprehensible, so full of gravity, that CC Sabathia would say he’s never been called that in any ballpark except Fenway?

The Red Sox were the last team to integrate, adding their first black player in 1959. Sox owner Tom Yawkey famously tried out Jackie Robinson in 1945, then allowed him and two other Negro Leagues players to be subjected to racist taunts from the stands. Yawkey’s reluctance to sign African-American players would, for years, be associated with the infamous Red Sox curse, eventually lifted in one of those grand “moments” in 2004. But racial animosity persisted at Fenway. In 2013, during the ALCS, a Red Sox fan allegedly screamed “Bye, Trayvon” at a Detroit Tigers fan. (Barry Bonds also refused to play there, telling the Boston Globe that the town was “too racist for me” and that “it ain’t changing.”)

Outside of sports, Boston has a checkered history when it comes to race. In 1965, the state of Massachusetts passed legislation requiring public schools in the state to integrate. After schools in Boston defied the law for nearly a decade, the NAACP sued the Boston School Committee and won. The subsequent busing plan led to flare-ups of violence and racial tension in the mid-1970s, just as the Red Sox, still owned by Yawkey, were on the rise in the American League. In 1975, they went to the World Series but lost to the Cincinnati Reds in seven games. That season, the Sox didn’t start a single African-American position player on Opening Day, though their Cuban pitcher, Luis Tiant, had a father who played in the Negro Leagues.

Read more at Bleacher Report.