By Jon Kawamoto—August 19 2019

When some Campolindo High School water polo players texted the N-word last fall, school officials moved quickly to deal head-on with the problem on the mostly white, suburban campus in Moraga.

The team members were not targeting anyone in particular, but an African-American team member was offended when he learned about it and told officials. In response, the coach canceled practice. Amy McNamara, associate superintendent at Acalanes Union High School District, was contacted and led a conversation about what had happened with the entire team, and how it was offensive to the African-American player.

“We did an activity around ‘othering’ and how people feel ‘othered’ in situations like this,” she said. “We had kids coming forward and admitting they were bullying. These were ninth-grade boys sharing really emotional stuff.”

Acalanes Union High School District in Lafayette — which includes the affluent cities of Orinda, Moraga and Lafayette, in addition to a portion of Walnut Creek — didn’t always have a clear way to deal with racist episodes until McNamara was hired in 2015.

Since then, the school district has taken several specific steps to address racism, sexism, bullying and other hurtful actions to students at its four high schools — Acalanes in Lafayette, Campolindo in Moraga, Las Lomas in Walnut Creek and Miramonte in Orinda.

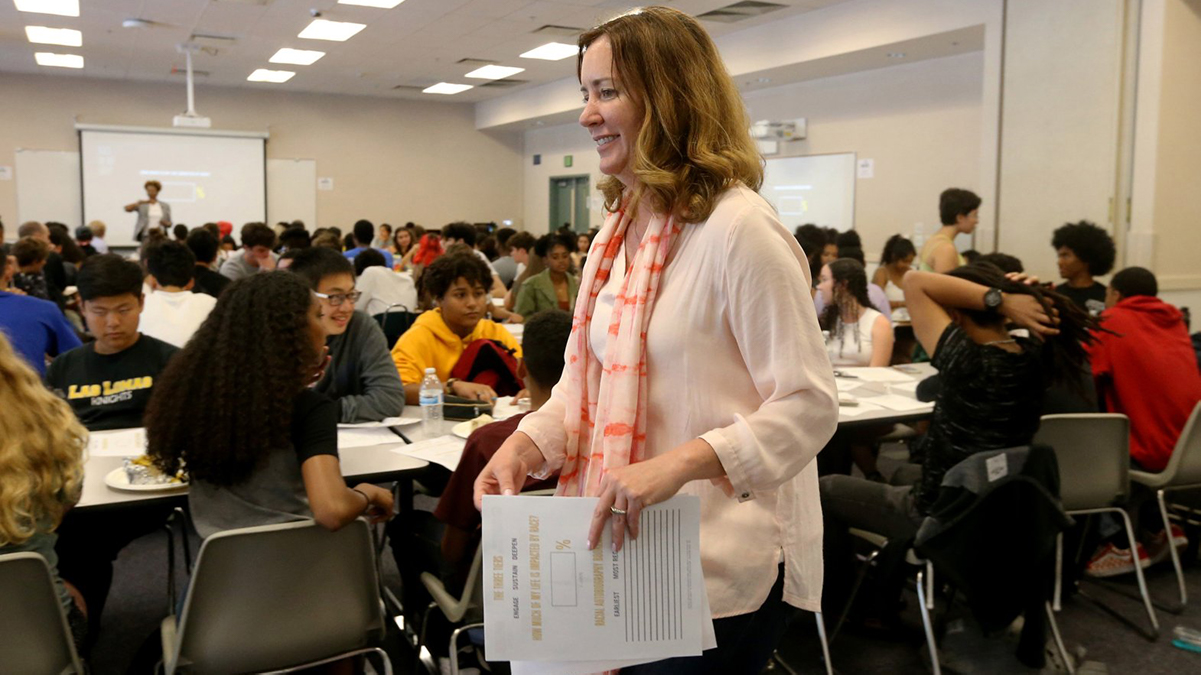

The district has also held annual districtwide diversity summits, bringing together about 100 students for a one-day retreat. The students discuss topics such as the N-word and other racist terms, the experience of immigrant students, queer culture and microaggression, or indirect, subtle or unintentional discrimination.

All of the district’s principals, most administrators and about 65 percent of the nearly 500 classified staff and teachers have taken two days of racial and equity training. The goal is for every district worker — including the bus drivers and clerical staff — to undergo the training. A strict procedure has been established to deal with racial episodes on campus such as what happened at Campolindo.

In addition, Acalanes Union High School District has begun reaching out about its racial and equity work to other area school districts, including Lafayette and Moraga elementary schools and the San Ramon Valley Unified School District. And the district has held forums for parents on race.

Acalanes Union High School District is a predominately white, affluent suburban district in Contra Costa County. The cities of Lafayette, Moraga and Orinda have a household median income of $139,018 to $186,075, according to 2017 U.S. Census statistics. Of the 5,662 students enrolled in 2017-18, 64.9 percent were white, 13.7 percent Asian, 9.9 percent Hispanic or Latino, and 1.7 percent were African American.

“We do need our kids as racially aware, socially just people that understand that not everybody’s experience is the same in this country and that largely is along the lines of skin color — why is that?” McNamara said. “You can be conservative, you can be liberal, but if you have a nuance of understanding about how race plays out in America and how it’s played out in our history and how it’s influenced our history, you’re going to be a much better-prepared person in our workforce. I believe it 100 percent.”

Shortly after she arrived in 2015, McNamara had to deal with a crisis — an African-American girl had been racially bullied at Las Lomas.

While not going into exactly what happened, McNamara said, “Students were thinking they were joking and it was not funny.

“This girl and her family were really hurt by it,” she continued. “What I realized was that the response from some of the staff, (including) one of the assistant principals — who’s no longer there — was not appropriate in terms of healing and addressing it in a way that I think would have had her feel like it mattered.”

A student who targeted the girl ended up being suspended.

McNamara said, “There were just patterns of insensitivity that were taking place across our district.” One was “White Out” at sporting events where students, parents and fans packed the stands in white T-shirts to show unity and intimidation. The tradition began in the 1980s. “But if you’re playing a team that’s largely kids of color from another district, it can feel very oppressive, very hostile,” said McNamara, who added “White Out” events ended before she arrived.

Another example, she said, was that schools were holding cultural fairs without student input. “So we sort of dressed in costume and put on a cultural fair without asking the Asian students or the Indian students to participate in them,” she said.

“I knew right away that we needed to do more. We really needed to start paying attention to these kinds of things that were happening and address them for us to be the highest performing district that we can be,” McNamara said. “We had to address that 40 percent of our students are not white. So if you’re not meeting the needs of everybody, we’re not as great as we can be.”

After the racial bullying episode at Las Lomas, McNamara approached the district’s diversity committee, made up of teachers and students from all four high schools. The committee was told to find 25 to 30 students at each school who wanted to talk about their racial experiences, and they shared them with the teachers.

“Young people are so open about talking about race — they’re not calcified like adults — and they just opened up,” McNamara said. “Students spoke about being ‘othered,’ feeling different, feeling ‘hypervisible.’ ”

The idea for a districtwide student diversity summit came out of that discussion.

“Campolindo is fairly closed-minded in terms of racial equity, and we have quite a ways to go,” said Lindsay Torres, a recent Campolindo graduate who will be attending Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. “Campolindo is overwhelmingly white, but incidents are fairly isolated. I don’t think it’s a hostile environment for a student of color to be in.”

Torres, then a student, led a workshop on immigrant students at the April diversity summit, chaired Campolindo’s equity committee and organized a cultural fair in May at the Moraga campus.

For all of the district’s work on racial and equity issues, problems still occur. But the district’s leaders deal with them swiftly in an organized fashion.

On Feb. 4, a racist note was discovered in an African-American male student’s binder. The student’s counselor was contacted, as was Campolindo Principal John Walker and McNamara. Walker visited all the student’s classes to talk about it and encouraged students to speak up.

Walker also did an investigation and met with parents, staff and 138 students. A staff meeting with a student diversity panel was held Feb. 6 to talk about the episode. The student who left the note was disciplined.

In addition, an anti-Semitic message was found in late January on a utility room door at the snack shack, enclosed by a fence and off-limits to students. The graffiti was about 3-by-5-inches, written in pen and somewhat faded, according to Walker.

The principal said an investigation wasn’t able to determine who wrote the graffiti.

“Campolindo High School will not tolerate racist or anti-Semitic language,” Walker said in his email. “Any alleged incidents involving this type of language lead to a full investigation by the school’s administrative team. If a student engages in inappropriate behavior related to racist language, the school assigns strong disciplinary consequences.”

McNamara praised the district’s efforts. “It’s really affirming for me that this district is a special place in terms of the willingness of staff to change practice, learn new things, try new things, to support our children,” she said.

The discussion of race has been a group effort, involving students, teachers, counselors, principals, administrators, classified workers and parents. But a key figure and catalyst is McNamara.

McNamara, with more than 20 years of experience as an educator, served previously as principal at James Logan High School in Union City, a more racially diverse school than those in Acalanes Union High School District. She has been a teacher in Fremont and an administrator in San Leandro.

She said her goal is “to always be an advocate and to help students. I know it sounds kind of cheesy, but I really feel that public education is the foundation of our democracy.”

To help with training, McNamara contacted Pacific Educational Group of San Francisco three years ago. The consulting firm works on racial equity with educational institutions, corporations, nonprofits and other organizations.

Pacific Educational Group founder and President Glenn Singleton and Lori Watson, an equity transformation specialist, praised and singled out Acalanes Union High School District for its work on racial and equity issues.

“In a nation that struggles to talk about race in a manner that is nuanced, insightful and generative, it is exceptional that a school system recognizes, embraces and acts upon the necessity to do so,” Singleton said in an email. “Acalanes Union is such a school system institution and has not retreated from this imperative.”

Read more at the East Bay Times.