By Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein—Sept. 27 2018

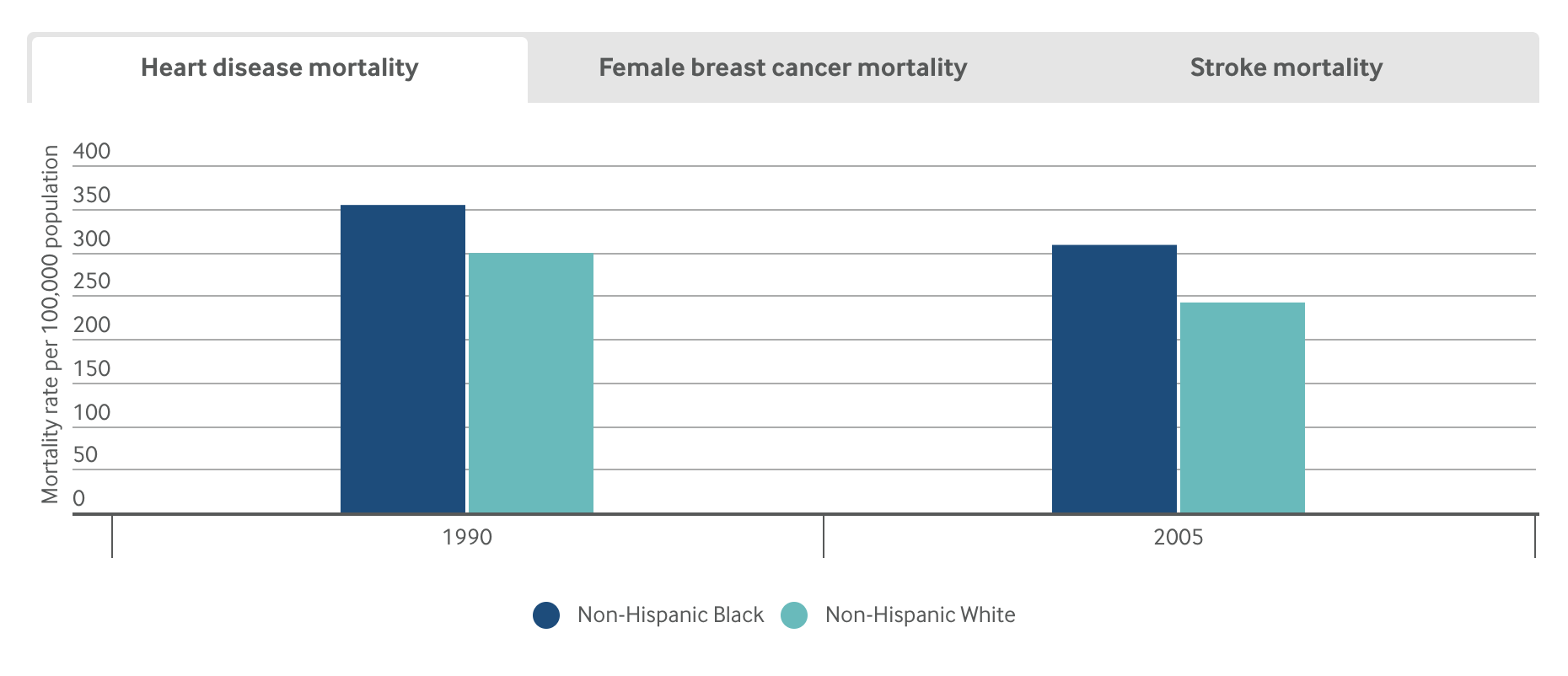

It’s been 15 years since the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s Unequal Treatment report, which synthesized a wide body of research demonstrating that U.S. racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventive medical treatments than whites and often receive lower-quality care. Most startling, the analysis found that even after taking into account income, neighborhood, comorbid illnesses, and health insurance type — factors typically invoked to explain racial disparities — health outcomes among blacks, in particular, were still worse than whites.

This research prompted the Institute of Medicine to add equity to a list of aims for the U.S. health care system, but efforts to ensure all Americans have equal opportunity to live long and healthy lives have been given less attention than have efforts to improve health care quality or reduce costs. A recent Institute for Healthcare Improvement white paper called equity “the forgotten aim,” noting as did the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, How Far Have We Come in Reducing Health Disparities?, how little progress has been made.

To reduce racial and ethnic health disparities, advocates say health care professionals must explicitly acknowledge that race and racism factor into health care. Less directed efforts to improve health outcomes, ones for instance that fail to consider the particular factors that may lead to worse outcomes for blacks, Hispanics, or other patients of color, may not lead to equal gains across groups — and in some cases may exacerbate racial health disparities.

Addressing social factors like unstable housing that can lead to poor health is important, but it’s also necessary to acknowledge past and present policies — redlining, eviction procedures, and disinvestment in low-income communities for example — that fuel housing instability. “As health care organizations, payers, and others focus on social determinants and population health, we have a responsibility to ask: To what degree are our approaches grounded in a framework that addresses structural racism and equity?” says Rishi Manchanda, M.D., president and CEO of Health Begins, a nonprofit that helps health care and community organizations address social determinants of health.1 “If we can’t answer that question with rigor and candor, even our most innovative solutions might perpetuate inequity and illness, not prevent it.”

In this issue of Transforming Care, we consider the roles of implicit bias and structural racism in creating and perpetuating racial health disparities. Implicit bias refers to learned stereotypes and prejudices that operate automatically and unconsciously, while structural racism takes into account the many ways societies foster racial discrimination through housing, education, employment, media, health care, criminal justice, and other systems. We focus on these factors more than interpersonal racism, or negative feelings or prejudices that play out between individuals, because while the latter is important the former are more likely to be undetected or unacknowledged factors. We offer examples of health systems that are making deliberate efforts to identify how implicit bias and structural racism play a role in their work, and developing customized approaches to engaging and supporting patients to ameliorate their effects. Many are taking part in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Pursuing Equity Initiative or have been recognized by the American Hospital Association’s Equity of Care Awards. Most of our examples relate to health disparities among black patients; we’ll delve into health disparities among Hispanics in a future issue.

Greensboro, N.C., is remembered as the site of one of the first “sit-ins” of the Civil Rights movement. In 1960, a group of black college students refused to leave a whites-only Woolworth’s lunch counter, coming back day after day. The incident garnered widespread attention and prompted similar protests across the South. The city’s role in desegregating health care is less well known. In 1962, George Simkins, Jr., a Greensboro dentist, and other black dentists, physicians, and patients filed a lawsuit claiming that federal support for the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and Wesley Long Hospital, local institutions that served only white patients, was unconstitutional. (One of Simkins’ patients had an abscessed tooth and needed surgery; Greensboro’s black hospital didn’t have space for him and the whites-only hospitals refused to treat him.) While the plaintiffs initially lost, they appealed, resulting in the Supreme Court decision, Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Hospital, that set in motion the desegregation of hospitals throughout the South.

In 2003, a group of Greensboro community organizers invited researchers from the University of North Carolina School of Public Health to form the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative, an effort to understand and address the lingering efforts of segregation. One of the group’s first activities was to conduct focus groups among black and white members about their health care experiences. Many said they had experienced discrimination in a health care setting, with several stories relating to women’s experiences with breast cancer treatment.

The group then conducted a study exploring how widespread such experiences were, and whether they affected breast cancer treatment outcomes. Community members helped develop the research questions, conduct interviews, and analyze the results. “This was an important piece of the collaborative,” says Christina Yongue, M.P.H., coordinator of the Greensboro Cancer Care and Racial Equity study. “We made sure the community had full participation in every step of the research process. This was because of historical distrust among black Greensboro residents for Cone hospital, and because of more general distrust of clinical research going back to Tuskegee.”

After this initial research, the collaborative sought to test whether customized supports could improve the experiences of black women undergoing treatment for early-stage breast cancer. They also examined the experiences of black men or women with early-stage lung cancer, in part to see whether black women’s experiences with breast cancer treatment were related to their gender as much as race. The Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative partnered with Cone Health’s Wesley Long Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Hillman Cancer Center in a project known as ACCURE (Accountability for Cancer Care Through Undoing Racism and Equity). Patients were randomly selected and invited to join the ACCURE study and then randomized into intervention and control groups. They found that at both cancer centers, black men and women with early-stage breast or lung cancer were less likely to complete treatment than white patients (81% of black patients completed treatment, compared with 87% of white patients), even after taking into account patients’ age, comorbid illnesses, health insurance, income, and marital status.

Read more at The Commonwealth Fund.